Medication Weight Gain Risk Checker

This tool estimates your medication's weight gain risk level based on clinical evidence from the article. Select your current or prescribed psychotropic medication to see estimated weight gain ranges and recommended actions.

Recommended Actions

Why Weight Gain Happens on Psychotropic Medications

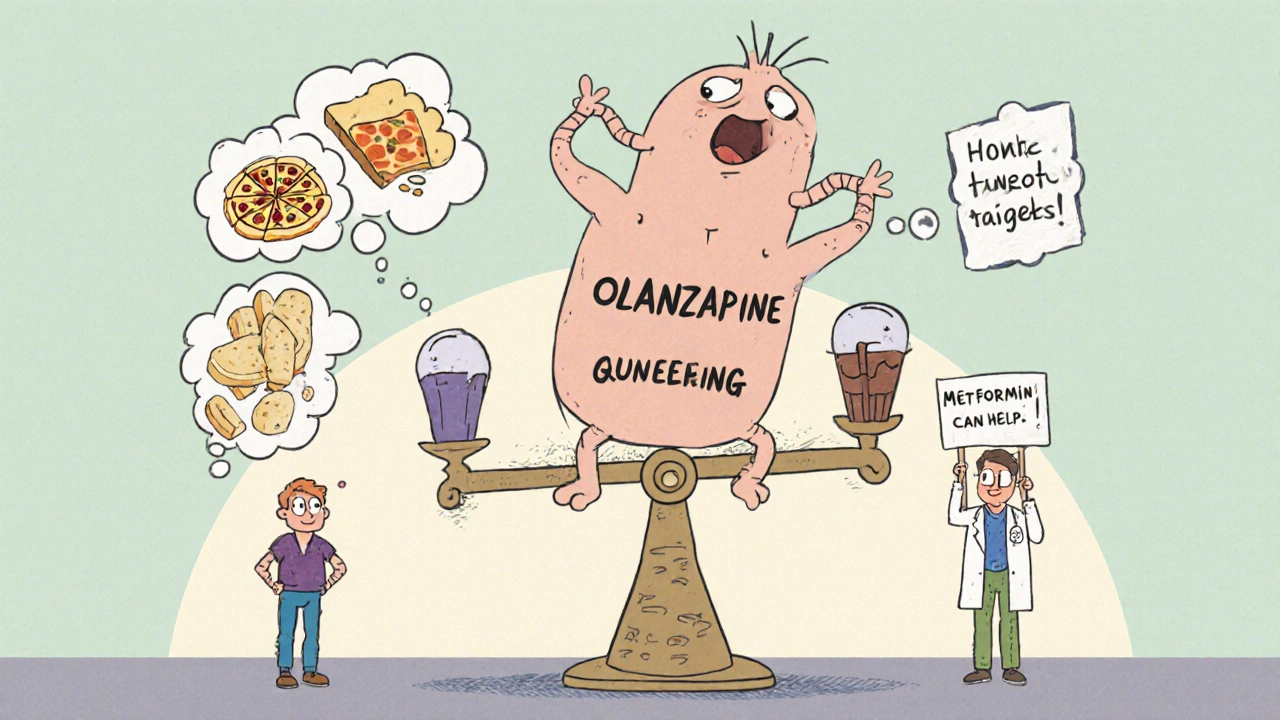

Many people start taking antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers to feel better-only to notice the scale creeping up. It’s not laziness. It’s not lack of willpower. It’s biology. Psychotropic medications change how your body handles hunger, metabolism, and fat storage. The most common offenders are second-generation antipsychotics like olanzapine and clozapine. In the first 10 weeks, people on these drugs often gain around 4 kg. By the end of the first year, gains of 10 kg or more aren’t rare.

This isn’t just about appearance. Weight gain from these medications increases the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. People with serious mental illness already live 10 to 20 years less than the general population-and medication-induced weight gain is a major reason why.

The science behind it is clear. These drugs block certain brain receptors-histamine-1, serotonin-2C, and dopamine-2-that normally help control appetite and energy use. When they’re blocked, you feel hungrier, crave carbs, and burn fewer calories. Some people even report feeling like their body is holding onto every extra bite.

Which Medications Cause the Most Weight Gain?

Not all psychotropic drugs affect weight the same way. Some are much heavier hitters than others.

- High risk: Clozapine and olanzapine lead the pack. Olanzapine causes weight gain in about 31% of users, while clozapine can trigger 5-10 kg gains in just months.

- Moderate risk: Quetiapine, risperidone, and paliperidone. These still cause noticeable gains, but less dramatically.

- Lower risk: Aripiprazole, ziprasidone, asenapine, and lurasidone. Lurasidone, for example, causes only 0.75 kg of weight gain on average-barely more than placebo.

Even among antidepressants, some are worse than others. Mirtazapine, amitriptyline, and paroxetine are known to pack on pounds. On the other hand, bupropion and fluoxetine tend to be weight-neutral or even slightly weight-reducing.

Mood stabilizers like lithium and valproate also contribute. Lithium slows metabolism, and valproate increases appetite. Neither is harmless when it comes to weight.

Why Losing Weight Is Harder When You’re on These Drugs

If you’ve ever tried to lose weight while on psychotropic meds, you know: it’s not like dieting for most people. A 2016 study tracked 885 people in a weight-loss program. Those on psychiatric medications lost 1.6% less weight over 12 months than those not on them. Only 63% of medicated patients hit the 5% weight loss goal, compared to 71% of others. For 10% loss? Just 32% made it, versus 41%.

Why? These drugs don’t just make you hungry-they make your body resist fat loss. Your metabolism slows down. Your muscles burn less energy. Even when you eat less and move more, your body fights back harder.

It’s not your fault. It’s not a lack of discipline. It’s a biological barrier built into the medication itself. That’s why standard weight-loss advice often fails here. You need a different strategy.

What Works: Proven Strategies to Fight Weight Gain

There are three main ways to manage this problem-and they’re not mutually exclusive.

1. Switch Medications (When Possible)

If your symptoms are stable, switching to a lower-risk drug can make a big difference. For example, switching from olanzapine to aripiprazole or lurasidone often leads to weight loss over time. One study showed patients lost an average of 3-5 kg after switching.

But this isn’t simple. You can’t just swap pills. Psychiatric stability comes first. If a drug is working well for your mood or psychosis, switching might risk a relapse. Talk to your psychiatrist. This decision needs careful planning.

2. Add Metformin

Metformin, a diabetes drug, is now one of the most studied tools for this problem. Multiple trials show it helps prevent or reverse weight gain caused by antipsychotics. People taking metformin alongside their psychiatric meds lost 2-4 kg more than those on placebo.

It works by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing appetite. Side effects are usually mild-stomach upset at first, but most people adjust. It’s not a magic pill, but it’s one of the few medications proven to directly counteract this side effect.

3. Use Topiramate or GLP-1 Agonists (Emerging Options)

Topiramate, originally an epilepsy drug, has shown promise too. Studies report 3-5 kg weight loss in people on antipsychotics. But it can cause brain fog or tingling, so it’s not for everyone.

Now, newer drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) are being tested in psychiatric populations. Early results show 5-8% body weight loss in just months. These were made for diabetes and obesity-but they’re now being explored for people on antipsychotics. More research is needed, but the potential is real.

Non-Drug Approaches That Actually Help

Medication changes and pills like metformin help-but they’re not enough alone. You need lifestyle support designed for your situation.

Structured Eating Plans

Psychotropic meds make you crave sugar and carbs. A standard low-calorie diet won’t cut it. You need a plan that accounts for increased hunger. Focus on high-protein meals, fiber-rich vegetables, and healthy fats. These keep you full longer and stabilize blood sugar.

Meal timing matters too. Eating at regular hours helps regulate appetite hormones. Skipping meals often backfires-leading to bingeing later.

Exercise That Fits Your Energy

You don’t need to run marathons. Even 30 minutes of walking five days a week helps. But if you’re dealing with depression or fatigue, start small. A 10-minute walk after lunch counts. Gradually build up.

Strength training is especially helpful. Muscle burns more calories at rest. Bodyweight exercises, resistance bands, or light weights can make a difference over time.

Behavioral Support

Working with a dietitian who understands psychiatric meds is key. So is therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps rewire automatic eating habits triggered by medication-induced cravings. Some clinics now offer integrated teams-psychiatrist, dietitian, therapist-all working together.

Monitoring Is Non-Negotiable

Waiting until you’ve gained 10 kg to act is too late. The American Psychiatric Association recommends checking weight, waist size, blood sugar, and cholesterol at baseline, then every three months after starting a new medication.

Write it down. Track your weight weekly. Note changes in appetite or energy. Bring this to your appointments. If your doctor doesn’t ask, ask them. You’re not being pushy-you’re protecting your long-term health.

What to Do If Your Doctor Won’t Listen

Too many people are told, “Just eat less,” or “It’s not that bad.” That’s not enough. This is a medical issue with real health consequences.

If your doctor dismisses your concerns:

- Bring printed evidence. Cite the 2017 APA guidelines or the 2020 NAMI report.

- Ask: “Is there a lower-risk medication that could work for me?”

- Request a referral to a dietitian who specializes in psychiatric medication side effects.

- Consider seeing a second psychiatrist if your current one doesn’t prioritize metabolic health.

You have the right to care that addresses both your mental and physical health. You’re not asking for a favor-you’re asking for standard care.

The Future Is Personalized

Scientists are now looking at genetics to predict who’s most likely to gain weight on certain drugs. Early studies point to variations in the MC4R gene-some people are just wired to be more sensitive to these side effects.

Digital tools are helping too. Apps like Moodivator, approved by the FDA in 2021, track food, mood, and activity. In a 2022 trial, users lost 3.2% more weight than those on standard care.

Health systems are catching on. The Veterans Health Administration now requires quarterly metabolic checks for everyone on antipsychotics. Result? 15% better early detection of problems.

You’re Not Alone-And It’s Not Your Fault

Weight gain from psychotropic medications is common, predictable, and treatable. But it’s not talked about enough. Many people stop taking their meds because they can’t handle the weight gain. That’s dangerous. Relapse can be worse than the side effect.

The goal isn’t to stop treatment. The goal is to treat both your mind and your body at the same time. With the right plan-medication adjustments, metformin, smart eating, movement, and support-you can manage your weight and keep your mental health stable.

It’s not easy. But it’s possible. And you deserve both.

Can you lose weight while on antipsychotics?

Yes, but it’s harder than for people not on these medications. Weight loss requires more structure, support, and often medication adjustments. Studies show people on antipsychotics lose less weight on standard programs-so you need tailored strategies like metformin, behavioral therapy, and lower-risk meds to succeed.

Which antipsychotic causes the least weight gain?

Lurasidone, aripiprazole, ziprasidone, and asenapine have the lowest risk. Lurasidone causes only about 0.75 kg of weight gain on average over a year-barely more than placebo. Aripiprazole is often a good switch from higher-risk drugs like olanzapine, especially if symptoms are stable.

Does metformin help with weight gain from psychiatric drugs?

Yes. Multiple clinical trials show metformin helps prevent or reverse weight gain caused by antipsychotics. On average, people taking metformin lose 2-4 kg more than those on placebo. It works by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing appetite. Side effects like mild stomach upset usually fade after a few weeks.

Should I stop my medication if I’m gaining weight?

No. Stopping psychiatric medication without medical supervision can lead to relapse, hospitalization, or worse. Instead, talk to your doctor about switching to a lower-risk drug, adding metformin, or starting a structured weight management plan. You can protect your physical health without risking your mental health.

How often should I check my weight on these medications?

Check your weight weekly at home and have your doctor measure it at every appointment. The American Psychiatric Association recommends checking weight, waist circumference, blood sugar, and cholesterol at baseline and every three months after starting a new psychiatric medication. Early detection makes intervention easier and more effective.

Ryan Anderson

November 14, 2025 AT 05:18Eleanora Keene

November 14, 2025 AT 16:49Joe Goodrow

November 14, 2025 AT 22:13Don Ablett

November 15, 2025 AT 09:39Kevin Wagner

November 15, 2025 AT 11:08gent wood

November 15, 2025 AT 21:58Dilip Patel

November 17, 2025 AT 07:54Jane Johnson

November 17, 2025 AT 08:13Peter Aultman

November 18, 2025 AT 10:55Sean Hwang

November 20, 2025 AT 02:37Barry Sanders

November 21, 2025 AT 21:49Chris Ashley

November 23, 2025 AT 14:15kshitij pandey

November 25, 2025 AT 02:40Brittany C

November 26, 2025 AT 06:56Sean Evans

November 26, 2025 AT 11:48