Getting the right dose of medicine for a child isn’t just about following a prescription. It’s about matching the drug to their body - not their age, not their size in clothes, but their actual weight. In pediatric care, weight-based dosing isn’t a best practice - it’s the only safe way to give most medications. A mistake of even a few milligrams can lead to serious harm, especially in babies and toddlers whose bodies process drugs differently than adults. That’s why hospitals and clinics rely on precise calculations and mandatory double-checks to keep kids safe.

Why Weight Matters More Than Age

For decades, doctors used age to guess a child’s dose. It was quick. Easy. But it was also risky. A 2-year-old weighing 12 kg and a 2-year-old weighing 20 kg? They’re the same age, but their bodies handle medicine in completely different ways. Studies show age-based dosing leads to errors in nearly 3 out of 10 cases, especially for kids at the extremes of growth. That’s why the American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidelines in 2022: weight-based dosing cuts medication errors by 43% compared to guessing by age.Every child’s body is different. Newborns have more water in their bodies - about 75% - compared to adults at 60%. That changes how drugs spread. Their livers and kidneys aren’t fully developed, so drugs stick around longer or clear too fast. A dose that’s perfect for a 60-pound child could be deadly for a 20-pound infant, even if they’re both labeled as “toddlers.” Weight-based dosing, measured in milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg), accounts for these differences. It’s not guesswork. It’s science.

The Math Behind Safe Dosing

There are three simple steps to get it right - but they must be done exactly.- Convert pounds to kilograms: Divide the child’s weight in pounds by 2.2. Do not round until the final answer. A child weighing 22 pounds is exactly 10 kg (22 ÷ 2.2 = 10). If you round too early - say, to 20 lbs = 9 kg - you’ve already introduced error.

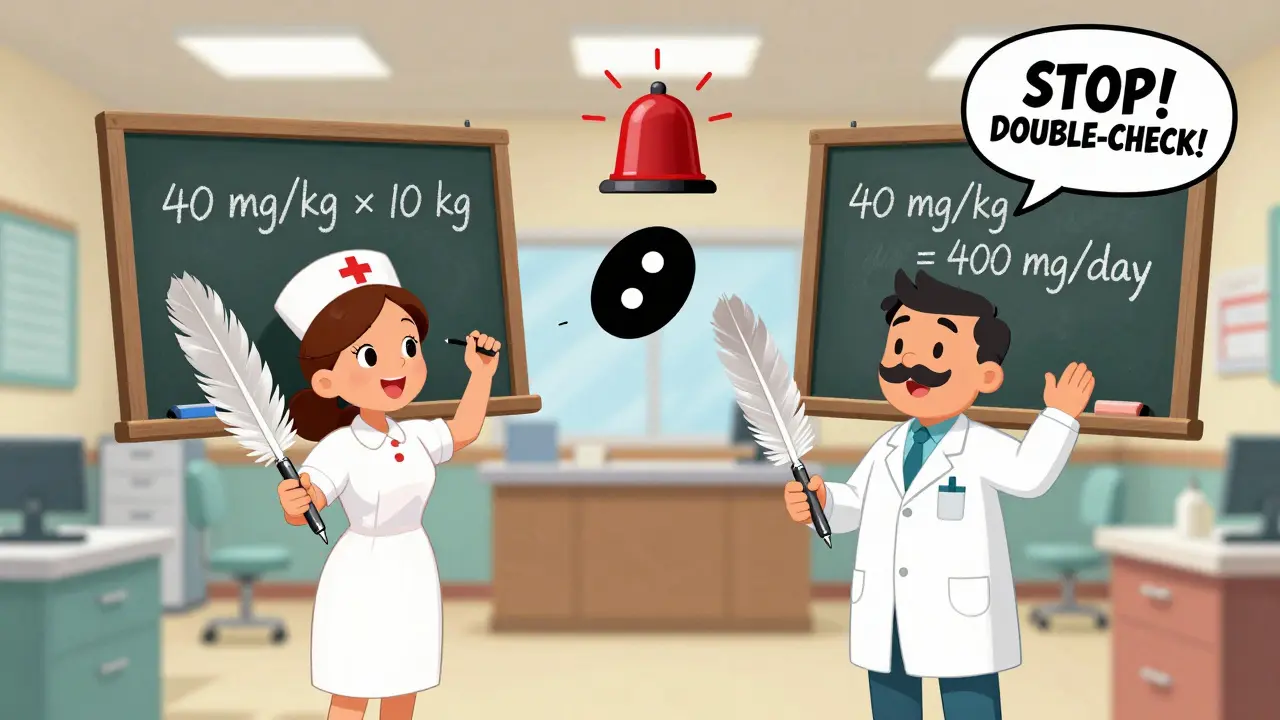

- Calculate total daily dose: Multiply the child’s weight in kg by the prescribed dose per kg per day. For example, amoxicillin at 40 mg/kg/day for a 10 kg child = 400 mg total per day.

- Split into doses: Divide the daily total by how many times it’s given. If it’s twice a day, each dose is 200 mg (400 ÷ 2).

That’s it. But here’s where things go wrong: using pounds instead of kilograms. In 2022, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that 32% of pediatric dosing errors came from unit mix-ups. One nurse accidentally gave a 10 kg child 200 mg of a drug meant for 20 mg because the scale was set to pounds. The system didn’t catch it. The nurse didn’t catch it. The child nearly had a seizure. After that, hospitals started putting bright red stickers on all scales: “WEIGH IN KG ONLY.”

The Double-Check That Saves Lives

Calculating the dose is only half the job. The other half is verifying it - independently, by someone else.The Joint Commission requires a double-check for all high-alert medications in children. That means two licensed providers - usually a nurse and a pharmacist, or two nurses - must independently calculate and confirm the dose before it’s given. This isn’t just a formality. A 2022 meta-analysis of 87,000 pediatric doses showed that double-checks reduce serious errors by 68%.

One nurse in Colorado shared how her team caught a 10-fold overdose. A resident ordered 200 mg of a drug for a 10 kg child. The calculated safe maximum was 40 mg/kg/day - so 400 mg total, or 200 mg per dose if given twice. But the drug’s label warned against exceeding 30 mg/kg/dose. That’s 300 mg max per dose. The resident’s order was 200 mg - technically within the daily limit, but over the per-dose limit. The double-check flagged it. The child was safe.

It’s not always that obvious. Sometimes it’s a decimal error: 10.0 mg instead of 100 mg. Or a misread weight: 15.5 kg instead of 155 kg. These mistakes happen. But they don’t have to.

When Weight Isn’t Enough

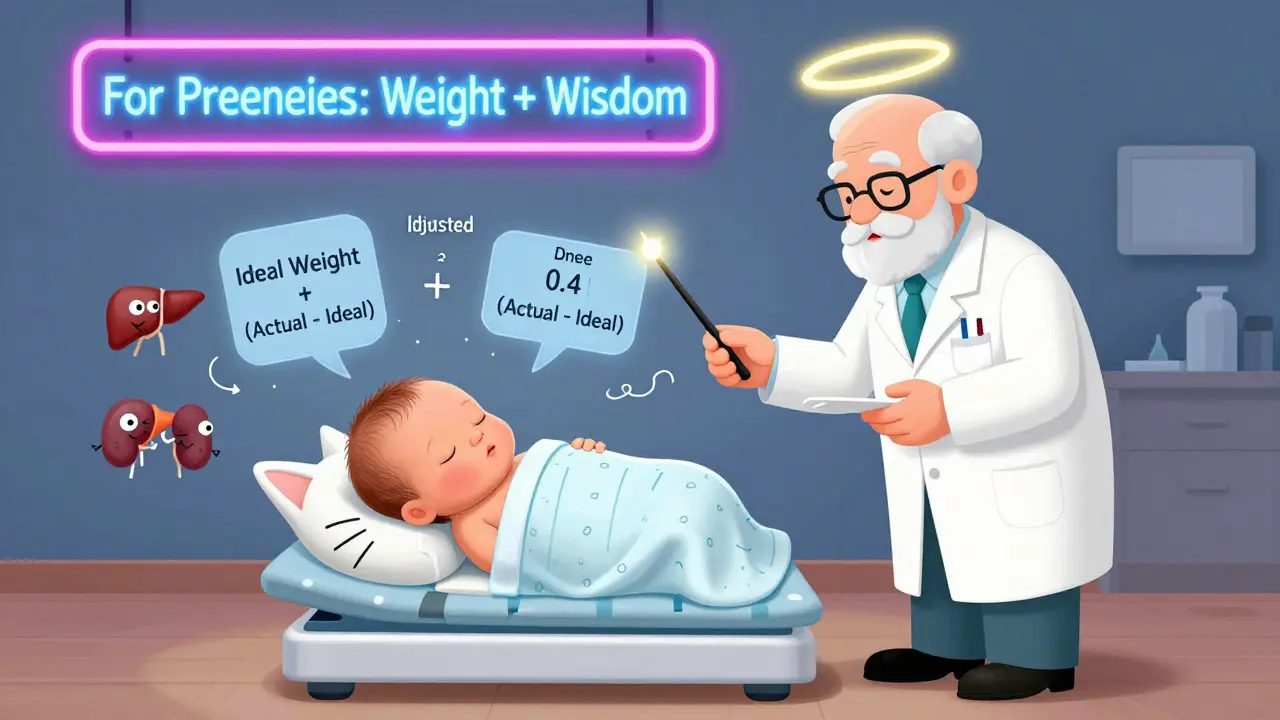

Weight-based dosing works for most drugs - antibiotics, pain relievers, seizure meds. But not all. For children with obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile), body fat changes how drugs behave. Water-soluble drugs, like many antibiotics, spread through body water. Fat doesn’t hold water. So giving the full weight-based dose to an obese child could lead to underdosing.That’s where adjusted body weight comes in. The Pediatric Endocrine Society recommends this formula: Adjusted Body Weight = Ideal Body Weight + 0.4 × (Actual Weight - Ideal Body Weight). Hospitals that use this method for certain drugs have reduced dosing errors by 31% in obese pediatric patients.

For chemotherapy drugs, body surface area (BSA) is sometimes used instead. The Mosteller formula - square root of (weight in kg × height in cm ÷ 3600) - gives more accurate doses for these powerful drugs. But it’s slower. It takes 47 extra seconds per dose. And it requires height measurement, which isn’t always easy with a crying toddler. So BSA is reserved for specific cases, not routine use.

And then there are neonates - babies under 6 months, especially preemies. Their kidneys and liver are still maturing. A 3 kg preterm infant might need 40-60% less of a drug like gentamicin than a full-term baby of the same weight. Weight alone doesn’t tell the whole story. Age, gestational age, and organ function matter. That’s why many NICUs use both weight and clinical judgment - and why every dose for a newborn is double-checked by a senior pharmacist.

Technology Is Helping - But Not Replacing People

Electronic health records now have built-in pediatric dosing tools. Epic Systems, Cerner, and others auto-calculate doses when you enter weight and drug. They flag doses that exceed safety limits. Some systems even cross-check with institutional guidelines. In 2023, 78% of children’s hospitals had these systems in place.But technology isn’t foolproof. One hospital reported a near-miss when a nurse entered 15 kg instead of 1.5 kg - the system didn’t flag it because 15 kg was “within range” for a 2-year-old. The error was caught because the nurse paused and thought, “That seems too high.” Human vigilance still matters.

That’s why training is non-negotiable. The Pediatric Nursing Certification Board requires all pediatric nurses to pass a 25-question dosing test every year - with a 90% minimum score. If you fail, you can’t give meds until you retrain. It’s strict. But necessary.

What Still Goes Wrong

Despite all the rules and tech, errors still happen. The most common ones in 2022, according to the ISMP:- 38%: Wrong unit (pounds vs. kilograms)

- 27%: Decimal point errors (10.0 mg vs. 100 mg)

- 19%: Not adjusting for kidney or liver problems

Emergency departments are the biggest risk zone. Nurses are rushed. Scales are old. Weights aren’t updated. One ER nurse in Texas told a story: a 5-year-old came in with a fever. The parent said the child weighed 40 pounds. The nurse wrote it down. The system auto-converted to 18.2 kg. But the scale was actually set to pounds - and the child weighed 80 pounds (36.4 kg). The dose was cut in half. The fever didn’t break. The child came back three days later with pneumonia. The error was caught only after the parents asked why the medicine didn’t work.

That’s why the best systems combine tech with culture. Red stickers on scales. Mandatory double-checks. Daily quick-reference charts on the wall. And a culture where anyone - even a student nurse - can speak up if something looks wrong.

The Bottom Line

Weight-based dosing isn’t complicated. It’s simple math. But it demands precision, attention, and teamwork. No one wants to be the person who gave the wrong dose. But mistakes happen - often because we assume someone else checked it.The truth is, safety isn’t a system. It’s a habit. It’s pausing before you press “administer.” It’s asking, “Did I convert correctly?” It’s having a second person look at the numbers. It’s knowing that for a child, 10 mg isn’t just a number - it’s the difference between healing and harm.

Every child deserves a dose that fits them - not a guess, not a shortcut, but the right amount, calculated right, verified twice. That’s the standard. And it’s not optional.

Why is weight-based dosing better than age-based dosing for children?

Weight-based dosing is better because children’s bodies vary widely in size, even at the same age. A 2-year-old weighing 12 kg and another weighing 20 kg have different body composition, metabolism, and organ function. Age-based dosing assumes all kids of the same age are the same - which leads to errors in nearly 30% of cases. Weight-based dosing, using mg/kg, matches the drug amount to the child’s actual physiology, reducing errors by 43% according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

What’s the correct way to convert pounds to kilograms for pediatric dosing?

Divide the weight in pounds by 2.2. Do not round the result until after you’ve completed the full calculation. For example, a child weighing 22 pounds is exactly 10 kg (22 ÷ 2.2 = 10). Rounding too early - like saying 20 lbs = 9 kg - can throw off the final dose. Always use the exact value until the final step to prevent cumulative errors.

What is a double-check protocol in pediatric dosing?

A double-check protocol means two licensed healthcare providers independently calculate and verify the medication dose before it’s given. One person calculates the dose; the second person recalculates using the same inputs. If the numbers don’t match, the dose is held until the discrepancy is resolved. This process reduces serious medication errors by 68% in children, according to the American College of Clinical Pharmacy.

Are there situations where weight-based dosing isn’t enough?

Yes. For obese children, body fat affects how drugs are distributed. Water-soluble drugs may need dosing based on adjusted body weight, not total weight. For chemotherapy, body surface area (BSA) may be more accurate. And for newborns - especially preemies - organ maturity matters more than weight. A 3 kg preterm infant may need 40-60% less of a drug like gentamicin than a full-term baby of the same weight. In these cases, weight is just one part of the equation.

What are the most common dosing errors in pediatric care?

The top three errors are: unit confusion (using pounds instead of kilograms - 38% of errors), decimal point mistakes (10.0 mg vs. 100 mg - 27%), and failing to adjust for kidney or liver problems (19%). These errors are preventable with proper training, clear labeling on scales, double-checks, and electronic alerts in the health record.

Phil Hillson

January 19, 2026 AT 08:12So basically we’re trusting nurses to do math in a high-stress environment and calling it healthcare

Christi Steinbeck

January 20, 2026 AT 02:55This is why I love pediatric nursing. Every dose is a tiny act of rebellion against chaos. We don’t guess. We calculate. We double-check. We save lives one decimal at a time.

Jacob Hill

January 20, 2026 AT 11:26I can’t believe how many hospitals still don’t have automated weight-to-kg converters built into their EHRs… it’s 2024, not 2004. Why are we still manually dividing by 2.2??

Lewis Yeaple

January 21, 2026 AT 14:22It is worth noting that the American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2022 guidelines, which are cited herein, are not legally binding; they are, however, considered the current standard of care. Failure to adhere may constitute negligence in a malpractice context.

Josh Kenna

January 22, 2026 AT 01:55Man I remember this one time I saw a nurse give a kid 10x the dose because the scale was in pounds and she didn't catch it… the mom started screaming and the kid just stared at the ceiling like 'what even is life'… we got lucky he didn't have a seizure

Valerie DeLoach

January 22, 2026 AT 16:20Weight-based dosing isn’t just science-it’s justice. A child’s body doesn’t care about their zip code, their insurance, or how loud their parents scream. It only responds to the math. When we get the math right, we honor their humanity. When we don’t, we betray them. No exceptions.

Jackson Doughart

January 23, 2026 AT 13:18The red stickers on scales… that’s the quiet revolution. No grand policy. No press release. Just a piece of tape and a collective refusal to pretend we’re doing better than we are.

sujit paul

January 23, 2026 AT 19:28One must consider the metaphysical implications of weight as a proxy for biological truth. In a world where algorithms dictate life, and kilograms replace soul, are we not reducing the child’s essence to a numerical value? Is safety merely the absence of error, or the presence of reverence?

Jake Rudin

January 24, 2026 AT 17:05Double-checks… yes… but why is it always the nurse and the pharmacist? Why not involve the parent? They know their child’s baseline better than anyone. A third set of eyes-especially the parent’s-could be the final safeguard we’ve overlooked.

Tracy Howard

January 25, 2026 AT 03:27Can we please stop pretending the U.S. is the only country that gets pediatric dosing right? In Canada, we don’t need red stickers-we have standardized protocols, mandatory training, and nurses who actually sleep more than four hours a shift. Also, we use metric. Obviously.

Aman Kumar

January 26, 2026 AT 06:28The system is broken. You have 15-year-old med students calculating doses while exhausted. You have EHRs that auto-calculate but don’t flag when someone types '15' instead of '1.5'. You have nurses who’ve been working 14-hour shifts. This isn’t a protocol issue-it’s a moral failure. We are gambling with children’s lives because we can’t afford to hire enough staff.

Lydia H.

January 27, 2026 AT 19:18I’ve seen a 2-year-old get the right dose because a student nurse asked, 'Wait… why does this feel heavy?' That’s the real magic. Not the tech. Not the stickers. Just someone who paused. And listened.

Astha Jain

January 28, 2026 AT 04:01lol i just saw a mom bring in a kid with a weight written on a napkin in lbs and the nurse just guessed… no joke

Malikah Rajap

January 28, 2026 AT 17:00Why don’t we just have a universal pediatric dosing app that pulls from the child’s EHR, auto-converts weight, cross-checks with drug databases, and sends a voice alert to the nurse saying 'THIS IS A 10X OVERDOSE, DO NOT ADMINISTER'? Why are we still using paper charts and hope?

Erwin Kodiat

January 29, 2026 AT 15:17It’s funny how something so simple-dividing by 2.2-can feel so heavy. But that’s the thing about medicine: the hardest parts aren’t the complex procedures. They’re the quiet moments where someone chooses to slow down. And does the math. Again.