When someone overdoses, every second counts. You might find a friend, stranger, or family member unresponsive, breathing shallowly, or not at all. Your immediate actions can mean the difference between life and death-long before 911 arrives. You don’t need to be a doctor. You just need to know what to do, and do it fast.

Step 1: Check Responsiveness and Breathing

Don’t shake or shout. That’s outdated advice and wastes precious time. Instead, tap their shoulder firmly and shout their name. If there’s no response, check their breathing immediately. Look for chest rise, listen for breath sounds, feel for air on your cheek. Do this within 10 seconds.Gasping, snoring, or irregular breaths aren’t normal breathing. These are signs of respiratory failure, common in opioid overdoses. If they’re not breathing normally-or not breathing at all-move to the next step right away.

Step 2: Call for Emergency Help

Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Even if you have naloxone, call first. Too many people skip this step because they think they can handle it alone. But EMS brings more than just a ride to the hospital-they bring oxygen, advanced airway tools, and medications that can reverse effects naloxone can’t touch.While you’re on the phone, put it on speaker. Don’t stop helping them. Tell the dispatcher what happened: “Someone stopped breathing after taking drugs.” Give your location clearly. If you’re unsure where you are, look for street signs, building numbers, or nearby landmarks. Every second matters.

Step 3: Give Rescue Breaths

If they’re not breathing, start rescue breathing. Tilt their head back slightly and lift their chin. Pinch their nose shut. Seal your mouth over theirs and give one slow breath-about one second long-until you see their chest rise. Don’t blow too hard; you don’t want air in their stomach. Wait five to six seconds, then give another breath.Keep going: one breath every five to six seconds. That’s about 10 to 12 breaths per minute. Don’t stop unless they start breathing on their own or help arrives. Most opioid overdoses cause breathing to slow or stop, but the heart keeps beating for a while. Rescue breathing keeps oxygen flowing to the brain. Brain damage can start after just four minutes without oxygen.

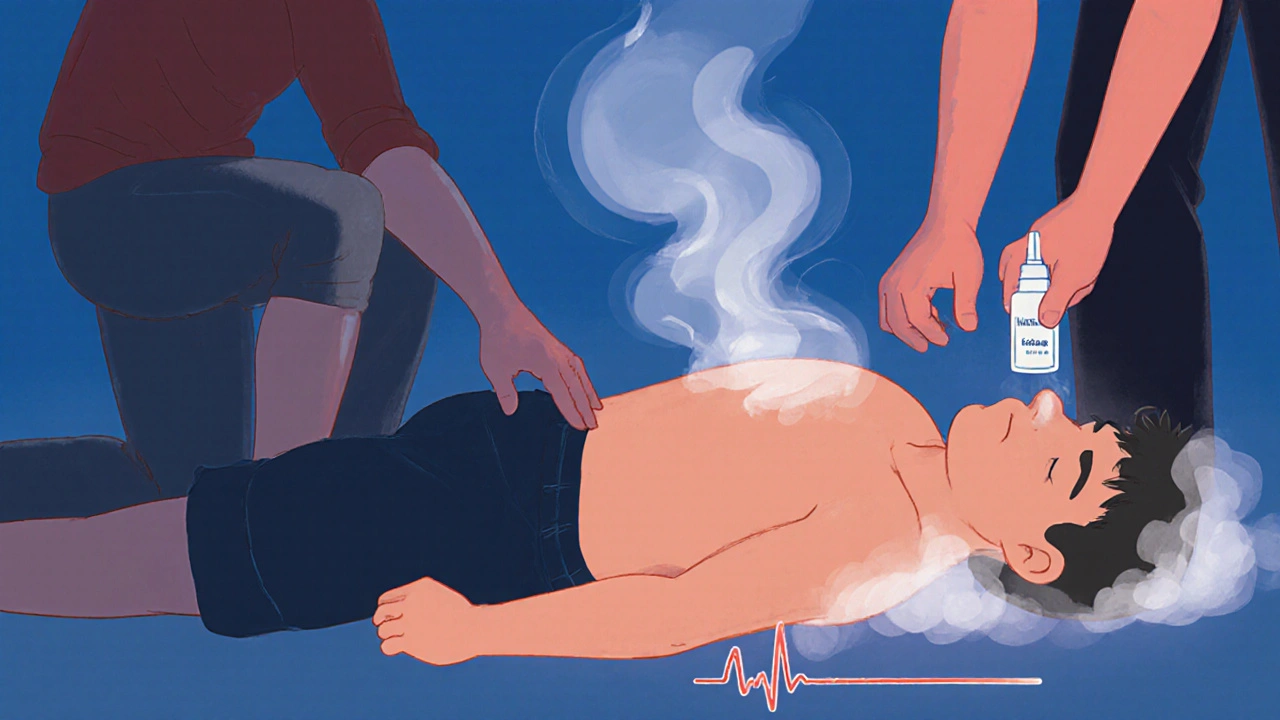

Step 4: Use Naloxone If You Have It

Naloxone reverses opioid overdoses. It won’t help with alcohol, benzodiazepines, cocaine, or methamphetamine overdoses-but if you’re not sure what was taken, give it anyway. Most overdoses involve opioids, especially fentanyl, which is now present in nearly 70% of fatal drug overdoses in the U.S.If you have nasal naloxone, spray one dose into one nostril while the person is lying on their back. You don’t need to switch nostrils unless instructed by the device. Some kits come with two doses-use the second one if there’s no response after 2-3 minutes. Naloxone wears off faster than some drugs, so even if they wake up, they still need medical care.

Don’t wait to see if they “wake up on their own.” If they’re unresponsive and not breathing properly, give naloxone and keep giving rescue breaths. Naloxone works quickly-usually within 2-5 minutes-but it’s not magic. It buys you time until EMS arrives.

Step 5: Place Them in the Recovery Position

If they start breathing on their own but are still unconscious, roll them gently onto their left side. This is the recovery position. It keeps their airway open and prevents choking if they vomit.To do it: Kneel beside them. Straighten their legs. Bend their far leg at the knee. Place their far arm under their head. Gently roll them toward you, keeping their head aligned with their spine. Tilt their head back slightly so the chin points up. Their top leg should be bent at 90 degrees to stabilize them. Check their breathing every few minutes.

Many people don’t know how to do this correctly. A 2023 study found that nearly 40% of bystanders couldn’t position someone properly without training. Practice it once-it takes less than 15 seconds once you’ve done it a few times.

What Not to Do

Don’t put them in a cold shower or ice bath. This is common advice for stimulant overdoses, but it’s dangerous. Sudden cold can trigger heart rhythm problems. Instead, remove excess clothing and fan them gently if they’re overheated.

Don’t try to make them walk, drink coffee, or “sleep it off.” These myths kill. If they’re unconscious, they’re in medical crisis-not sleeping.

Don’t leave them alone. Even if they seem fine after naloxone, their condition can crash again. Stay with them until paramedics arrive.

Recognizing Different Types of Overdose

Not all overdoses look the same. Opioids (heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone) cause slow or stopped breathing, blue lips or fingernails, pinpoint pupils (though fentanyl often doesn’t cause this), and extreme drowsiness.

Stimulants (cocaine, meth, MDMA) cause high body temperature, rapid heartbeat, confusion, seizures, or violent behavior. Their skin may be hot and dry. Cooling them down gently with wet cloths on the neck and armpits helps-but don’t use ice.

Alcohol overdoses cause slow, irregular breathing, vomiting, cold/clammy skin, and unconsciousness. The biggest danger is choking on vomit. That’s why the recovery position is critical.

Why This Works

Studies show bystander intervention cuts overdose deaths by up to half. In communities where people are trained in these steps, survival rates jump from 87% to nearly 99%. The CDC tracked over 12,500 overdoses reversed by laypeople using full protocols-only 1.3% ended in death before hospital arrival.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about acting. Even if you only do rescue breathing and call 911, you’ve done enough. Naloxone is a tool, not a requirement. The most important thing is to never wait.

What to Expect After Help Arrives

Paramedics will give oxygen, monitor vital signs, and may give more naloxone. They’ll check for other issues like low blood sugar, seizures, or heart problems. The person will likely be taken to the hospital for observation-even if they seem fine. Overdose can cause delayed complications, especially with fentanyl or mixed substances.

They may be scared, embarrassed, or angry. Don’t lecture them. Say something simple: “I’m glad you’re okay.” Support matters more than judgment.

Can naloxone hurt someone who didn’t overdose?

No. Naloxone only works on opioids. If someone hasn’t taken opioids, it has no effect. It’s safe to use even if you’re unsure. Giving it to someone who didn’t overdose won’t harm them.

How long does naloxone last?

Naloxone lasts 30 to 90 minutes. Many opioids, especially fentanyl, last much longer. That’s why someone can wake up after naloxone and then slip back into overdose. Always stay with them until help arrives and tell paramedics you gave naloxone.

What if I’m afraid to call 911 because of legal trouble?

All 50 U.S. states and the U.K. have Good Samaritan laws that protect people who call for help during an overdose. You won’t get arrested for possessing small amounts of drugs if you’re seeking help. Emergency responders are there to save lives, not punish. Calling 911 is the right thing to do-and legally protected.

Can I overdose someone by giving too much naloxone?

No. You can’t overdose on naloxone. Giving more than one dose is safe if the person doesn’t respond. Some people need two or three doses, especially with strong opioids like fentanyl. Follow the instructions on the kit.

Where can I get naloxone?

In the U.K. and many U.S. states, naloxone is available without a prescription at pharmacies. Some community health centers and harm reduction programs give it out for free. Ask your local pharmacy or public health office. It’s becoming as common as an EpiPen.

Next Steps After the Emergency

Once the immediate danger passes, think ahead. If you’re someone who uses drugs-or know someone who does-consider carrying naloxone. Keep it in your bag, coat pocket, or car. Check the expiration date every few months. Practice the steps with a friend. Watch a 10-minute training video on the CDC or SAMHSA website.

Overdose isn’t a moral failure. It’s a medical emergency. And the most powerful tool we have isn’t a drug or a device-it’s a person who knows what to do and isn’t afraid to do it.

farhiya jama

November 28, 2025 AT 11:12Astro Service

November 28, 2025 AT 18:54DENIS GOLD

November 29, 2025 AT 21:17Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 1, 2025 AT 18:22Daniel Rod

December 3, 2025 AT 05:03gina rodriguez

December 4, 2025 AT 07:20Sue Barnes

December 4, 2025 AT 21:55Barbara McClelland

December 5, 2025 AT 16:21Alexander Levin

December 6, 2025 AT 11:08Ady Young

December 7, 2025 AT 15:26Travis Freeman

December 9, 2025 AT 11:35Sean Slevin

December 10, 2025 AT 21:23Chris Taylor

December 12, 2025 AT 00:38Melissa Michaels

December 12, 2025 AT 08:48Nathan Brown

December 13, 2025 AT 03:14Matthew Stanford

December 14, 2025 AT 18:53Olivia Currie

December 15, 2025 AT 04:54Curtis Ryan

December 15, 2025 AT 06:14