Just because a brand-name drug’s patent expires doesn’t mean you can walk into a pharmacy and buy the cheaper generic version the next day. There’s a long, tangled process between that patent clock hitting zero and the first generic bottle appearing on the shelf. For many people, this delay feels like a hidden tax - a system that lets drugmakers stretch profits while patients wait for affordable options. The truth? It’s not just about waiting. It’s about legal battles, regulatory hurdles, and strategic delays that can push generic availability out by years.

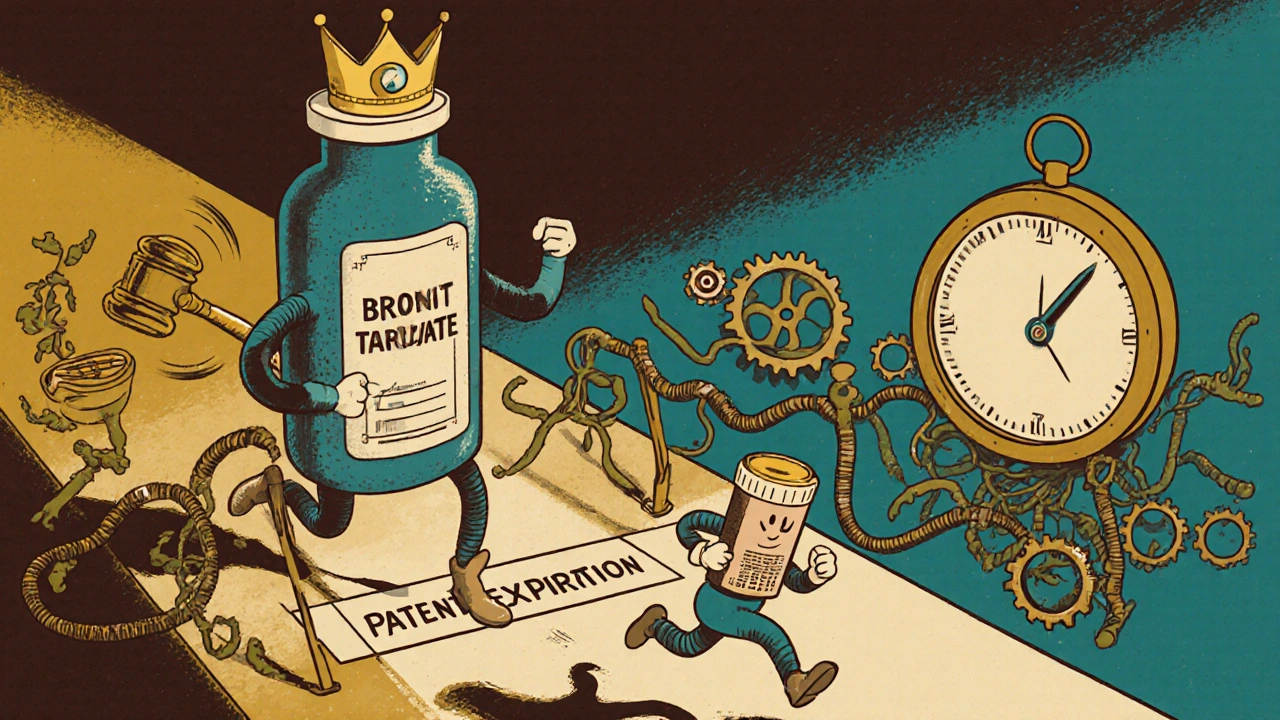

Patent Expiration Isn’t the Finish Line

Most people assume that when a drug’s 20-year patent runs out, generics can immediately enter the market. That’s not how it works. The patent clock starts ticking the day the drug is first filed - not when it’s approved or sold. By the time a drug reaches the market, 8 to 10 years of that 20-year patent are already gone. That leaves only 7 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity before generics can legally challenge it. But even then, it’s not over. The FDA adds layers of exclusivity on top of patents. A new chemical entity gets 5 years of protection. If the manufacturer runs new clinical trials for a different use, that’s another 3 years. Orphan drugs - those treating rare conditions - get 7 years. And if they test the drug on kids, they get an extra 6 months. These aren’t loopholes. They’re written into law. Together, they can delay generic entry for over a decade, even after the original patent expires.The ANDA Pathway: A Shortcut, But Not a Fast Track

Generic manufacturers don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. Instead, they file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), proving their version is bioequivalent - meaning it works the same way in the body. Sounds simple, right? Not quite. The FDA took an average of 25 months and 15 days just to review an ANDA in recent years. That’s over two years before approval, even if there are no legal issues. For complex drugs - like injectables, inhalers, or topical creams - it can take even longer. And the FDA approved 1,165 generic drugs in 2021, but only 62% actually hit the market within six months of approval. Why? Because approval doesn’t mean you can sell.Patent Litigation: The Real Bottleneck

The biggest delay isn’t the FDA’s review time. It’s patent lawsuits. When a generic company files an ANDA, they must certify that the brand-name drug’s patents are either invalid or won’t be infringed. This is called a Paragraph IV certification. It’s a legal bomb. The brand-name company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - unless the court rules faster. Here’s the catch: most lawsuits don’t end in 30 months. The average time from lawsuit filing to a final appeals court decision? Over 37 months. And even after the court rules, generic companies often wait. Why? Because if they launch before a final decision, they risk massive damages if they lose. So they sit on approval, waiting for the legal dust to settle. Research shows that, on average, generic drugs launch 3.2 years after the 30-month stay expires. That means the patent may have expired years ago - but the generic still isn’t on the shelf.

Patent Thickets and Strategic Delays

Brand-name companies don’t rely on just one patent. They build patent thickets - dozens of overlapping patents covering everything from the active ingredient to the pill coating to how it’s made. A single drug might have 14 or more patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. Each one is a potential legal roadblock. Drugs with more than 10 patents take, on average, 37% longer to face generic competition. Cardiovascular drugs, with their complex formulations, see delays of 3.4 years after patent expiration. Dermatology drugs? Just 1.2 years. It’s not about medical complexity alone. It’s about money. High-revenue drugs - those making over $1 billion a year - face an average of 17 patent challenges. Low-revenue drugs? Only 8. The bigger the profit, the more patents get thrown up to block generics.The 180-Day Exclusivity Trap

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity. No other generics can enter during that time. Sounds fair? It’s not. That 180-day window creates a race. The first filer has to launch within 75 days of FDA approval - or they lose the exclusivity. Many don’t make it. Why? Manufacturing issues. Quality control. Supply chain problems. In 2022, 22% of first filers forfeited their exclusivity because they couldn’t scale production fast enough. Another 10% lost it due to legal setbacks. Meanwhile, other generic companies sit back. Why rush? They wait for the first one to clear the path - and then jump in right after the 180 days end. That means even after the first generic launches, you might not see more options for months.Reverse Payments and Secret Deals

Sometimes, the brand-name company doesn’t sue. They pay the generic maker to stay away. These are called reverse payment settlements - and they’re legal, for now. The brand pays the generic company millions to delay launching their cheaper version. The FTC estimates these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that secret settlements could violate antitrust laws. But they’re still happening. About 45% of delayed generic entries were tied to these deals before the ruling. And while fewer are happening now, they haven’t disappeared. A 2022 Congressional report found that these settlements still delay generic entry by an average of 2.1 years.

Why Some Generics Come Fast - and Others Never Do

Small molecule drugs - the kind you swallow in a pill - typically see generics within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But biologics? Those are different. They’re complex proteins made from living cells. The law created a separate approval path called biosimilars, but it’s slower. It takes an average of 4.7 years for a biosimilar to launch after the reference biologic’s patent expires. And then there’s patent evergreening. Companies make tiny changes - a new coating, a different dosage form, a new delivery device - and file a new patent. A 2024 study found that 68% of brand-name drugs get at least one new patent within 18 months of the original expiring. That resets the clock. Again.What’s Changing? And What’s Not

The FDA is trying. Under GDUFA II, they promised to cut review times for complex generics from 36 months to 24. But as of mid-2024, only 62% of applications met that goal. The CREATES Act helps generics get samples of brand-name drugs to test against - something companies used to refuse. The Orange Book Transparency Act forces companies to list patents more accurately - reducing disputes by 32% in its first year. AI is being tested to speed up bioequivalence studies. If it works, it could cut development time by 25%. Biosimilars are gaining ground - they’re expected to capture 45% of the biologics market by 2030, saving $150 billion a year. But the core problem remains. Even with all these reforms, the median time from patent expiration to generic availability is still 18 months. For millions of Americans, that’s 18 months of paying $500 for a drug that could cost $30. That’s not innovation. That’s a system designed to protect profits - not patients.What You Can Do

If you’re paying for a brand-name drug with a patent that expired over a year ago, ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic available yet?” If not, ask why. Sometimes, it’s just a supply issue. Other times, it’s legal delays. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book online to see what patents are still active. Support policies that push for faster generic entry - like banning reverse payments and requiring faster FDA reviews. Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion a year. But that only works if they actually reach the market.Why don’t generic drugs appear immediately after a patent expires?

Generic drugs don’t launch right after patent expiration because of legal and regulatory delays. Brand-name companies often sue generic manufacturers who challenge their patents, triggering a 30-month FDA approval hold. Even after that, manufacturing, quality control, and market strategy can delay launch. On average, generics appear 18 months after patent expiration - sometimes longer.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generics?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the modern system for generic drug approval. It lets companies file abbreviated applications (ANDAs) without repeating clinical trials, as long as they prove bioequivalence. It also gives brand-name companies patent protection and exclusivity periods, while offering the first generic challenger 180 days of market exclusivity. It balances innovation with competition - but the system is often exploited to delay generics.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement a generic manufacturer submits with its ANDA, claiming that a brand-name drug’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, the FDA can delay approval for up to 30 months - making this the most common reason for delayed generic entry.

Do all drugs have the same delay before generics arrive?

No. Small molecule drugs usually see generics within 1.5 years of patent expiration. Complex drugs like injectables or inhalers take longer - often over 2 years. Biologics, which are large protein-based drugs, face the longest delays, averaging 4.7 years. Drugs with many patents (called patent thickets) or those protected by orphan or pediatric exclusivity also take significantly longer.

What’s the difference between a generic drug and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs made from chemicals. Biosimilars are highly similar - but not identical - copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. Because biologics are harder to replicate, biosimilars require more testing and have a slower approval process. That’s why they take nearly five years to reach the market after the original biologic’s patent expires.

Can I check if a generic is coming for my medication?

Yes. The FDA’s Orange Book lists all approved drugs and their patents. You can search it online to see if any generic applications have been filed and whether patents are still active. Your pharmacist can also help - they often know when generics are expected to launch based on FDA updates and manufacturer announcements.

Kihya Beitz

November 15, 2025 AT 04:42Wow. So we’re paying $500 for a pill that costs $3 to make, and the only thing stopping generics is lawyers and corporate greed? Classic. I swear, if you replaced ‘pharma’ with ‘Big Oil’ in this article, it’d read exactly the same. Same playbook. Same victims. Same bullshit.

David Rooksby

November 16, 2025 AT 11:47Let’s be real - this whole system is engineered by the same people who made sure your Wi-Fi router has a 10-year patent on the color of its casing. Patent thickets? Reverse payments? The FDA taking 25 months to review a generic? That’s not bureaucracy - that’s a cartel with a law degree. And don’t get me started on how they use orphan drug status like a cheat code. One company got 7 extra years for a drug that treats a disease affecting 12 people. TWELVE. Meanwhile, insulin prices are still rising. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with IV drips.

Teresa Smith

November 16, 2025 AT 20:09The real tragedy here isn’t the delays - it’s how normalized they’ve become. We accept 18 months of price gouging as ‘the cost of innovation.’ But innovation doesn’t mean locking patients out of affordable medicine. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to balance access and incentive - not turn drug patents into a Monopoly board where the only winners are the ones who own the most squares. We need structural reform, not band-aids like the CREATES Act. Ban reverse payments. Cap exclusivity extensions. Force transparency. This isn’t rocket science - it’s basic fairness.

Danish dan iwan Adventure

November 17, 2025 AT 10:39ANDA review times are a red herring. The real bottleneck is the 30-month stay triggered by Paragraph IV certifications. That’s not regulatory - that’s litigation theater. And the 180-day exclusivity window? A rigged game. First filers are incentivized to delay launch to extract maximum rent. It’s not competition - it’s collusion with a paperwork trail.

Ankit Right-hand for this but 2 qty HK 21

November 19, 2025 AT 07:50India makes 40% of the world’s generics and still waits for US patent expiry? Pathetic. You people let pharma run your healthcare like a feudal lord. We’ve been making cheap insulin for 15 years - why can’t you just import it? Your system is broken because you’re too lazy to fix it.

Jennifer Walton

November 20, 2025 AT 00:51It’s not just about patents. It’s about the commodification of health. When life-saving medicine becomes a financial instrument, the human cost is invisible until you’re the one holding the bill.

Daniel Stewart

November 21, 2025 AT 04:22There’s a deeper irony here - the same people who scream about ‘government overreach’ are perfectly fine with patent monopolies enforced by courts and regulatory delays. The system isn’t broken - it’s working exactly as designed. For someone.

Melanie Taylor

November 22, 2025 AT 05:51OMG this is so true!!! I’ve been paying $400 for my blood pressure med for 2 years after the patent expired!!! My pharmacist said ‘it’s pending’ but then I checked the Orange Book and there were ZERO patents listed!!! I was so mad I cried in the parking lot 😭

ZAK SCHADER

November 24, 2025 AT 03:26Why do we even have the FDA? If generics are bioequivalent why does it take 2 years to approve them? I mean cmon. It’s just a pill. Let people buy it. The market will sort it out. This is why America sucks at healthcare - too many rules for simple things.

Jamie Watts

November 25, 2025 AT 16:01Patent evergreening is the real villain here. Companies tweak a pill’s coating and call it a new drug? That’s not innovation that’s fraud. And the 180-day exclusivity? It’s a trap for the first guy who tries to do the right thing. The whole system is rigged to protect the rich and punish the sick

Latrisha M.

November 26, 2025 AT 17:23If you're paying for a brand-name drug that expired over a year ago, ask your pharmacist. They often know more than your doctor. And check the FDA's Orange Book. Knowledge is power - and it might save you hundreds.

Oyejobi Olufemi

November 28, 2025 AT 08:22Let’s be honest - the only reason generics are delayed is because the U.S. government is owned by Big Pharma lobbyists. You think this is about science? No. It’s about money. And the people who profit from this system? They live in mansions while you ration your pills. This isn’t capitalism. It’s a criminal enterprise with a DEA license.